If you were to go back in time, to the days when the great pre-Colonial Filipino warriors walked the earth, do you believe your combat skills would look like theirs? Would Lapu Lapu recognize the sinawali or your favorite sumbrada drills? Would you feel confident defending your family against the muskets and razor sharp swords and lances wielded by Spanish conquistadors who looked at you as no more human than a boar? Could you convince a Datu to allow you to teach his warriors to go into battle?

I guess my question is if you believe that your FMA is as deadly as your websites say they are? Do you honestly feel like a lion walking among the lower animals, like a natural killer? Are you simply a businessman engaged in the lucrative product called “self defense”? Or do you see this arts as simply a hobby or alternative to Pilates or Yoga?

When you train, do you train casually or like a fanatical madman?

When you spar/fight, do you often laugh and hold conversation, or do you treat every match or sparring session like a deathmatch?

Do you consider yourself a “modern” martial artist, or an “old school” Eskrimador/Arnisador?

The business of teaching the Filipino arts is very new. Prior to the 1970s there wasnt much tradition established in the way of running an actual martial arts school. You could probably count on your hands and feet how many Eskrima masters were actually making a living teaching their arts in commercial locations, save for a few who taught Eskrima alongside their Karate, Judo or Aikido clubs. While we do have many traditions and customs in our arts concerning conduct and interactions, we really don’t have much of a tradition that governed the best way to teach our arts and to teach entire student bodies. Even in many of today’s Guros back home in the Philippines, many outside of the larger organizations learned our art almost exclusively one-on-one from our parents, uncles, grandparents and masters. We may have excelled because our teachers had sparring matches in their day, but hauled us off to tournaments–and did not have to deal with much politics or competition. In our learning, we did not have many classmates to train with, share ideas with, compete against. Some of us never had the privilege of befriending fellow Eskrimadors from other styles and schools, because our Lolo was the only Eskrimador in town (or he saw established Arnis clubs as competition).

I said all of that to make this point: The FMAs have largely been developed in the last 3 or 4 decades, and did so in a vacuum. We are still very young as an industry despite that our arts have been around as long as man has. This shift–from isolated art passed nearly father-to=son, to an art that has taken the global martial arts community by storm–has left us with some growing pains and many interdisciplinary conflicts and disagreements about what is best for young Arnisadors and Silat fighters of today:

- learn a style thoroughly and master it before moving on to other arts

- one must learn several types of disciplines (weapon base, empty hand, grappling base) arts to become “complete”

- cross train to experience other arts

- you must fight full contact or you aren’t fighting at all

- you mustn’t fight with rules or you aren’t doing FMAs at all

- “Oh, we have that too, in our style”

- you need drill to build skill

- you don’t need drills, just skills

- style need belts and forms

- the only belts you need are championship belts and the only form you need is perfect form (this one is mine lol)

- this art can be learned via distance learning or seminar series

- if you aren’t training in person, you aren’t really learning

- I’ve never heard of that master, he must be a nobody

- just because he’s popular, doesn’t mean he’s the best

- what?? your master never been to the Philippines??

- the americans have the most progressive FMA

I could go on. But I think you get it.

These types of discussions are very commonplace in the arts; such philosophical disagreements will always remain. However, unlike other arts, we have not been around long enough to see the outcome of years of various approaches come to fruition in order to truly make a judgment about them, based on actual results. Consider for example, the Mixed Martial Arts field. When they first hit the scene in the mid-90s, everyone concluded that “Stand up fighting is dead; it loses to Brazilian Jujitsu every time.” This was based on the outcome of a few fights the world watched, yet no one noticed that the organizer of the fights was the intended champion’s brother. He didn’t find the “best fighters on the planet” to fight his brother. He found refridgerator repairmen, he found aging amateur boxers, out-of-shape karate Black belters and declared them “Kenpo Masters”, in the world of actual champion fighters, he scheduled only one: a 50 year old Grandmaster and former full contact fighter, Grandmaster Ron van Clief. There was no invitation for the current killers of the day, such as Dennis Alexio, Maurice Smith, and Andy Hug to participate. But simply based on what we saw, most martial artists immediately assumed that no martial artist could “stand up” to grappling. Then, in came kickboxer Maurice Smith. At that time, he was the first real kickboxer to enter the cage, and many grapplers of his time had never felt the kind of power a professional Muay Thai expert could generate. Where MMA guys once thought one could simply block a round kick and then duck underneath punches to take your opponent down–they discovered that a round kick could break your arm. We then changed our belief to “One needs Muay Thai AND grappling, Karate is useless…” Years later (and I predicted it right here on this blog in 2009!) MMA fans got to meet Karate Black Belter Lyota Machida, who proved that you could win against MMA fighters with good old traditional Shotokan Karate. With a background of ten years of traditional point-style karate, Machida learned to close long ranges of distance much quicker than kickboxers and MMA fighters generally fought from. This, plus the fast tempo of point style fighting, gave Machida a great advantage due to speed, timing and tactics that many inside the cage had never seen. This allowed him to knock fighters out in both the K-1 as well as the octagon who were once thought too skilled to be taken out with backfists and round kicks. After what I call the “Age of Discovery” for MMA fans and fighters, you see that today there are fighters of all backgrounds, even Aikido and boxing, using their skills to some degree of advantage in the ring… and once upon a time, these arts were thought to be completely useless in the cage. Full circle, we endured two decades of misconceptions to arrive at the idea that perhaps, it really IS the fighter and not the style.

Likewise, in the Filipino arts, we must hold our own experiments, arguments, discussions, and discoveries. And like many traditional arts, we must reject the “classical FMA mess” that our masters and even we have propogated and believed–in order to bring our thinking up to the modern times and into something practical and pragmatic. I wrote an entire series on this subject alone, entitled “Liberate Yourself from Classical FMAs”–a six part series you might want to check out. It is based on the notion that perhaps our teachers may be wrong about some things they taught us. Like any martial artists who might have told his students in 1996 that “Karate loses to BJJ on the street” or “99% of all fights go to the ground”–we must come to terms with the idea that yes, we were wrong, and we must update our thinking. In the FMAs we have such misconceptions that range from the extreme to the plain old lackadaisical:

- if it doesn’t involve broken bones, it isn’t Eskrima at all

- with drills, you don’t need sparring because all sparring have rules

- you could learn Eskrima and defend yourself with no physical strength at all

- fitness is irrelevant with a knife in your hand

- we train for killing only

- one could actually learn Arnis in 4 weeks or 8 seminars and teach

- if you have never fought in an Arnis tournament, you’ll never be able to use it for self defense

(The items on this list, by the way, are all things I’ve actually witnessed FMA people telling students)

And here is the truth. Full contact fighting is necessary. One needs to experience the stick as a potentially bone-breaking weapon to completely understand Eskrima’s potential and what can happen if it is trained properly. However, in order to fight full contact, you will either have to train in a way that you must pad/protect yourself from real injury, alter the rules, or actually put yourself in harm’s way to gain this understanding. There is no way you could fight this way and get the amount of sparring necessary to develop your reflexes to transfer your stick skills to knife fighting. Knife fighting, which most FMA people never engage in, requires the most amount of timing and reflexes before it becomes useful to you. The drills knife practitioners use hardly qualifies as “sparring” and honestly do nothing for one’s fighting skill if we are talking about a real fight where one of you may die. Out of all the weapons, this aspect of the FMA needs the most sparring to develop, yet it is the one Eskrimadors practice the least. The closest substitute, or transferable skill, would be point fighting with the stick. Not quite as fast as knife fighting, Stick point fighting develops great eye-to-hand coordination, and teaches you the most about target awareness and protecting things we ignore in the full contact stick fighting, like the belly, the throat and the wrist. Not exactly targets one would pursue in stickfighting, but all you need is one good slash on any of those targets, and you don’t just lost the fight… you die. I have fought in perhaps 20 Arnis tournaments in my life, and never once have I ever been thrusted or cut on my throat or belly, and honestly, the times I was hit on the wrist it might have been by accident lol. And please, let’s not even get into the subject of FMA empty hand. But I will say this: Every Eskrimador claims to do empty hand. But when was the last time you attended an Arnis tournament and they actually FOUGHT with their hands at said tournament?

Competition fighting is vital because we all need to experience the psychological threat of winning and losing, the sting to our egos when we realize that there are fighters out there better than we are, and perhaps the nervousness of having several fighters we may actually fear–but we face them anyway three or four times a year. This cannot be developed in the classroom, and it sure won’t come from a beloved classmate. There are many benefits to fighting strangers in a stressful, uncomfortable, unfamiliar setting. Why? Because that is life, and the FMAs are not a spectator sport–nor is it a pastime. You must be a participant.

And then there is the subject of training. Do you train until your hands blister and your forearms cramp? And then wait two days for them to heal and do it all over again? What is your maximum number of strikes you can throw before your shoulder gives out? Do you even KNOW what your maximum number of strikes is?

Training is another aspect we must explore in order for Eskrima to evolve. Most of us train in sessions where we sweat and tire, but never train until we drop. Do you understand what type of art Arnis actually is? I think not, for most people. Many of us treat the Arnis as if it were a majorette’s baton. We twirl and twirl, and some of us even twirl to music (yuck). We have the neatest ways to strip a stick or make it go flying. I’ve seen Eskrimadors fly through the air to take away a stick, do something like a cartwheel in a disarm, one guy looked like he was break dancing or doing some kind of Tony Jaa moves to disarm his opponent’s stick. Yet at the core of Eskrima is the very real skill of taking a bolo and slicing once to amputate the opponent’s forearm or halfway behead the opponent at the neck. We should be able to take a simple rattan stick and crush the opponent’s skull with a downward hit, sever his carotid artery by smacking the side of his neck, hit him in the temple and force his eye out the socket. Unfortunately, many of your grandmasters were so enthralled in keeping up with Grandmaster Dan Inosanto’s beautiful displays of sinawali and knife to hand translations, I doubt any of your grandmasters can actually behead a goat’s carcass with a bolo or even pop a watermelon with a 1″ rattan. These are skills the Eskrimador of the 1970s did; I watched them myself, and practiced on a 4×4 as a teen until I could do them myself. Have you even tried to break a watermelon with a stick?

I have long said that at a minimum, an advanced Eskrimador should be capable of throwing 500 repetitions of his system’s basic hits in one sitting. In my basic system, we have 6 strikes; in my complete system we have 24. I would like to suggest that when you get done with this article and the other articles I tagged, that you take ONE of your style’s hits, and do them 500 times. If you cannot, then you have your first goal in bringing your Eskrima to the 21st Century. The days of stick twirling and living with impractical views of Eskrima should be over. The Arnis by VHS phase should be over. Chakos are cute, but they are not what this art is all about. Filipino arts are not to be performed to rap or house music, they are not to be done with acrobatics, they are not about getting points and medals and trophies and certificates and the most youtube likes and shares. Before we discuss technique and demonstrations of possiblities with fighting, you must first ensure that you have developed your ability to use your stick/blade/sword/hand in a way that it destroys whatever it comes in contact with. Practicing a stick twirl is pointless if you can barely dent a watermelon with it. Get the lethal capability to use your weapons without the drills and techniques and combinations and forms–and then we can discuss all of that other stuff.

The Filipino art, at its core, is a simple art born of the stick, the machete, the dagger, and the empty hand. It was designed to stop a man from injuring your family in the most violent un-Christian, un-Islamic, brutal way possible. It was not developed to enable practitioners the false pride of being able to brag that you “kicked someone’s ass” or to go around starting fights. Arnis does not have much of a code like the I-Ching or Samurai code; Filipinos are simple, friendly, loving people. Yet we have a side that if you’ve made yourself an enemy, your family’s bloodline stops at you… and it does so in the worst of ways.

Now, of all you do in the arts–does your training live up to that philosophy?

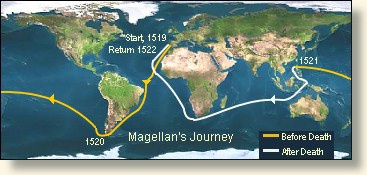

Rather than inspire yourself from the writings of modern experts at selling DVDs and seminar certifications, let’s go back 500 years. Read what your country’s enemies said about the spirit of the people who created this art. Hopefully it will give you some insight into the kind of enemy your attackers should encounter in the unfortunate event that they choose to attack you. History fans may be familiar with it; this is the eyewitness account of Magellan’s death–from the point of view of Antonio Pigafetta, written April 27th, 1521–in his own words:

“When morning came, forty-nine of us leaped into the water up to our thighs, and walked through water for more than two cross-bow flights before we could reach the shore. The boats could not approach nearer because of certain rocks in the water. The other eleven

men remained behind to guard the boats. When we reached land, those men had formed in three divisions to the number of more than one thousand five hundred persons. When they saw us, they charged down upon us with exceeding loud cries, two divisions on our flanks and the other on our front.

When the captain saw that, he formed us into two divisions, and thus did we begin to fight. The musketeers and crossbow-men shot from a distance for about a half-hour, but uselessly; for the shots only passed through the shields which were made of thin wood and the arms [of the bearers]. The captain cried to them, “Cease firing cease firing!” but his order was not at all heeded. When the natives saw that we were shooting our muskets to no purpose, crying out they determined to stand firm, but they redoubled their shouts. When our muskets were discharged, the natives would never stand still, but leaped hither and thither, covering themselves with their shields. They shot so many arrows at us and hurled so many bamboo spears (some of them tipped with iron) at the captain-general, besides pointed stakes hardened with fire, stones, and mud, that we could scarcely defend ourselves.

Seeing that, the captain-general sent some men to burn their houses in order to terrify them. When they saw their houses burning, they were roused to greater fury. Two of our men were killed near the houses, while we burned twenty or thirty houses. So many of them charged down upon us that they shot the captain through the right leg with a poisoned arrow. On that account, he ordered us to retire slowly, but the men took to fight, except six or eight of us who remained with the captain.

The Death of Magellan, from

a 19th century illustrationThe natives shot only at our legs, for the latter were bare; and so many were the spears and stones that they hurled at us, that we could offer no resistance. The mortars in the boats could not aid us as they were too far away.

So we continued to retire for more than a good crossbow flight from the shore always fighting up to our knees in the water. The natives continued to pursue us, and picking up the same spear four or six times, hurled it at us again and again. Recognizing the captain, so many turned upon him that they knocked his helmet off his head twice, but he always stood firmly like a good knight, together with some others. Thus did we fight for more than one hour, refusing to retire farther. An Indian hurled a bamboo spear into the captain’s face, but the latter immediately killed him with his lance, which he left in the Indian’s body. Then, trying to lay hand on sword, he could draw it out but halfway, because he had been wounded in the arm with a bamboo spear. When the natives saw that, they all hurled themselves upon him. One of them wounded him on the left leg with a large cutlass, which resembles a scimitar, only being larger. That caused the captain to fall face downward, when immediately they rushed upon him with iron and bamboo spears and with their cutlasses, until they killed our mirror, our light, our comfort, and our true guide. When they wounded him, he turned back many times to see whether we were all in the boats. Thereupon, beholding him dead, we, wounded, retreated, as best we could, to the boats, which were already pulling off.”

At a minimum, your FMA training should leave you terribly strong; possessing a good control over your anger so that even your screams can frighten your enemies; you should fear no man; pain and suffering should not paralyze you; your strikes, hits and thrusts should be destructive and swift; your feet should be quick, strongly balanced and evasive; your body must be hard and durable; your tolerance for pain should be heightned to a mind-numbing level. You must learn from those who know about the body and how to destroy it to make your Eskrima more effective. (For example, to crush an eye socket, you must learn more than simply the angle used. There are very specific areas around the eye that will give you the injury intended. Go too high, you end up with not much more than a laceration or leaving the opponent with a knot. See the two illustrations above and hover your cursor over the images) It is these things–not fancy drills, forms, twirls and disarms–are what the FMAs can give the practitioner safety and dominance in combat. In order to achieve them however, the modern Eskrimador must design everything in his training to reach these goals. And sorry to disappoint, but weekend seminars and patty-cake-with-a-stick won’t get you there.

This is the philosophy I was raised in, and is the basis for everything you find on this blog. I implore you: Take a look at how you train. Many of the things your masters teach will point you in this direction, but many of them do not. You must find the middle ground to even things you may dislike, like hand conditioning and live stick sparring; but you must do them. Hopefully, in the next decade or so–we will end up with Eskrimadors and Arnisadors our ancestors would recognize.

Thank you for visiting my blog. And don’t forget to check to our our books!

men remained behind to guard the boats. When we reached land, those men had formed in three divisions to the number of more than one thousand five hundred persons. When they saw us, they charged down upon us with exceeding loud cries, two divisions on our flanks and the other on our front.

men remained behind to guard the boats. When we reached land, those men had formed in three divisions to the number of more than one thousand five hundred persons. When they saw us, they charged down upon us with exceeding loud cries, two divisions on our flanks and the other on our front.